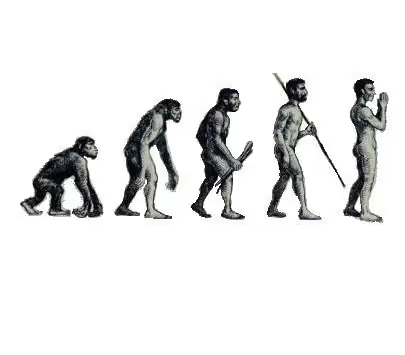

Some years ago, I approached my upcoming supervisor in Germany with a dissertation project exploring the viability of religion-related brain studies, back then called neurotheology. My scientific mentor liked the idea and topic, but he was also wise and fair enough to give me a warning: “If you dare to play with the biologists, you are probably forfeiting all chances of getting a chair in the future.” It was a time when the “E-word” was whispered rather than discussed among those exploring religion from a scientific perspective. Some of the older colleagues liked to quip that the last time they heard about evolution was in school – and that they were glad about it. Of course, it was perfectly okay to study secular evolutionism vs. religious creationism from a sociological perspective and to snicker knowingly about these enjoyable “Culture Wars” in the United States. But at the same time, it was almost forbidden to explore the evolution of human religiosity and religions from an evolutionary perspective. I did it nevertheless and never regretted the choice.Thus, it felt kind of special to be invited to Wuppertal University featuring a small congress organized by German anthropologists on the Philosophical Anthropology of Religion as an Interdisciplinary Field of Research. While the bold and able organizers, Prof. Gerald Hartung and Dr. Matthias Herrgen, didn’t mention the E-word in the headlines, it was clearly present in the logo showing a primate evolving into a praying human. I felt deeply honored as this very image had been the illustration of a popular article of mine about Die Evolution des Homo religiosus. There was clearly something on the move: One could watch the crumbling of worn-out taboos and fears.And the conference demonstrated that anti-evolutionist sentiments are slowly receding throughout the scientific disciplines. Although all of us had our fair share of bad experiences with people fearing evolutionary studies instead of really understanding them, we felt more than rewarded to see how far those very studies have brought us empirically. From Psychologist Prof. Matt Rossano (Southeastern Louisiana) to Protestant Theologian Prof. Wolfgang Achtner (Gießen) right to his colleague in Philosophy, Dr. Ulrich Frey and empirical Anthropologist Prof. Christoph Antweiler (Bonn), the common understanding, terms, and shared data brought about solid talks and a lively exchange on the evolved biological, cultural, and metaphysical aspects of humanity. I thoroughly enjoyed discussing the data and implications of religious demography with a range of very diverse colleagues, bound together by curiosity and a viable scientific perspective. In fact, the common ground turned out to be solid enough to start a shared book project, aimed at bringing the findings and results to a wider, English-reading public. Of course, we’ll let you know here at TVOL when it is published.Yes, to most of us participating in the anthropological sciences in a wider sense, progress seems to be awkward, slow, and quite often unfair. But after I returned from Wuppertal, I realized that upcoming generations probably will have to consult with a history department in order to understand the taboos and fears that have surrounded interdisciplinary evolutionary studies far too long.

April 26, 2014

Homo Religiosus

Related Posts

No items found.