How we act upon the world depends upon how we conceptualize the world. Life is far too complex to pay attention to everything. Instead, our ideas draw our attention to a tiny slice of reality and process this information in ways that “make sense;” in other words, that help us to survive and thrive in the world to which we are so largely blind.

The multiple crises facing the world today are therefore symptoms of a crisis taking place inside our heads. Our ideas are failing us. Perhaps they served us better in the past, or served at least some of us, but now they seem poised to bring about the ruin of us all.

It’s not just a matter of good or bad intentions. Even the best-intentioned person can behave ruinously based on ideas that “made sense” to them but didn’t happen to play out as intended in the real world. Such a person is like the character of a folk tale who is granted a wish and ends up regretting what they wished for.

The phrase “new paradigm” is often used to convey the need for a way of thinking that is truly different and not just a nudging of current ways of thought. Yet, the concept of paradigms is notoriously fuzzy, and even people who are highly aligned in their good intentions differ in their articulation of what “the” new paradigm might be. If the concept of a new paradigm becomes too pluralistic, then the word paradigm loses its meaning.

This essay has two goals: The first is to provide an operational definition of the word “paradigm” that captures the idea of multiple sets of ideas guiding action. My second goal is to identify both an old paradigm that needs to be shed and a new paradigm that needs to be adopted. I see this in broad historical terms as a transition from the individualism and reductionism of past centuries to the holism and interactionism of the 21st century.

The overall tone of my essay is optimistic. There really is a new way of thinking that has emerged over roughly the last 50 years, which can help us navigate the world much better than older patterns of thought. The new paradigm is not something we need to search for or bring about in the future. It already exists for a sizeable community of thinkers and doers—although this community is a tiny fraction of those who need to know about it. Hence, the urgent need is to catalyze something that is already in progress.

A short essay cannot do justice to such large issues. Rather than write something longer, I have elected to state my argument as briefly as possible and rely upon some of my colleagues who represent the new paradigm to add their perspectives. I do not expect them to agree with me or each other on all points. As we shall see, complete agreement is not expected for any paradigm. Instead, my hope for this essay and commentaries is to accelerate awareness and adoption of the new paradigm at a moment in world history when time is of the essence.

I will attempt to make progress along the following fronts:

• Provide an operational definition of the word paradigm.

• Understand paradigms as containers for productive disagreement.

• Establish two criteria for evaluating a given paradigm.

• Articulate and evaluate the currently dominant paradigm in economics and the social sciences.

• Identify the problem of no paradigms.

• Articulate and evaluate a new paradigm that can be widely agreed upon.

• Reach a consensus on the new paradigm.

• Use the new paradigm to inform how we act upon the world across all scales and spheres of activities where positive change is needed.

An operational definition of the word paradigm: The word paradigm is so fuzzy that, according to Masterman (1970), the philosopher Thomas Kuhn used it in 21 different senses all by himself! For our purposes, I propose the following operational definition:

Paradigm: An interlocking set of ideas that makes sense of the world but also blinds us to other possibilities.

The “interlocking set of ideas” part of the definition conveys the idea that a paradigm systematically organizes the perception and processing of information about the world in a way that informs action. The “blinds us to other possibilities” part of the definition conveys the idea that paradigms are separated from each other in ways that make it difficult to get from one to the other. Hence, the need for “paradigmatic change” rather than “incremental change”.

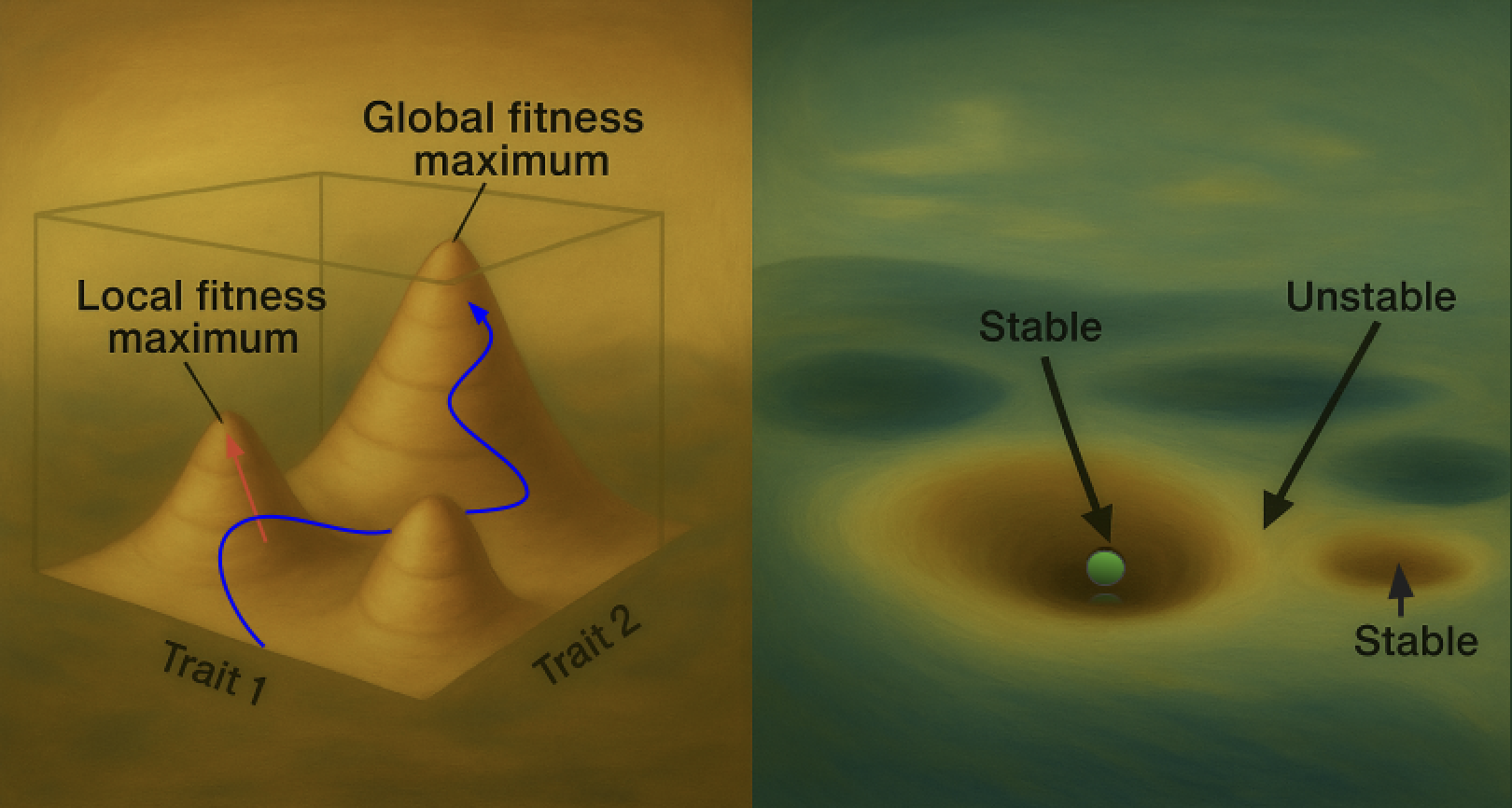

Two visual metaphors convey our operational definition (See Figure 1). The first is the metaphor of an “adaptive landscape” from evolutionary theory, where natural selection is imagined as a hill-climbing process on a landscape of multiple peaks and valleys. It is capable of adapting organisms to their environments to a degree (climbing a given peak), but has difficulty evolving from one peak to another.1

The second metaphor, from complex systems theory, imagines dynamical systems as a ball placed on a surface with multiple pits, or “basins of attraction”. Each basin is a local equilibrium that resists incremental change, like a ball being displaced only partway up the side of its bowl. A larger displacement is required to move from one bowl to another.

These two metaphors are not exactly equivalent, since nonliving physical systems can have multiple basins of attraction, and a Darwinian process of variation, selection, and replication is required to climb adaptive peaks. Nevertheless, they both provide a way to visualize the two notable features of paradigms: their internal coherence and their separation from other paradigms.

Understand paradigms as containers for productive disagreement: It is a mistake to suppose that everyone operating within a given paradigm agrees with each other. For Kuhn, a given paradigm is where “normal” science takes place. The point is that a shared understanding of the world in some respects is required for people to productively disagree in other respects. An example is the interlocking set of ideas that became known as the Modern Synthesis in evolutionary biology, which was centered on Mendelian genetics and largely excluded the study of development and other Darwinian processes such as human cultural evolution (Provine 1971). A great deal of productive disagreement took place within the confines of the Modern Synthesis, in the form of proposing and testing alternative hypotheses.

Eventually, what the synthesis left out began to claim more attention, leading to terms such as “evo-devo” (Goodman and Coughlin 2000), “the extended evolutionary synthesis” (Laland et al. 2015), and “generalized Darwinism” (Aldrich et al. 2008). These new paradigms opened up new arenas of “normal” scientific inquiry, to which the Modern Synthesis had been blind.

Two criteria for evaluating a given paradigm: Any interlocking set of ideas can be evaluated according to two criteria: conformance to factual knowledge and informing appropriate action. The first is the standard criterion for evaluating scientific paradigms. The second is the standard criterion for evaluating policies that are enacted in the world, defined broadly as “a course or principle of action adopted or proposed by a government, party, business, or individual”.

A given paradigm can score high or low on either criterion. Many scientific paradigms only attempt to describe what is and make no effort to prescribe what ought to be done. Many policies are based on experience or nonscientific belief systems and make little effort to become anchored in scientific knowledge. Increasingly, however, there is a need for our paradigms to score high on both criteria. The best of our scientific knowledge is required to address the complex problems of our age.

Articulate and evaluate the currently dominant paradigm. In economics and many other policy domains, the currently dominant paradigm is variously described as “orthodox”, “neoclassical”, and “neoliberal”, based on an atomistic conception of human nature labelled Homo economicus and social dynamics that are at equilibrium. Here is how it is described in an article titled “Economics as Universal Science” (Heilbroner 2004, p 615).

“Economics has become the imperial social science…Its formal mode of argument, mathematical apparatus, spare language, and rigorous logic have made it the model for the ‘softer’ social sciences.”

This passage and the title of the article from which it is drawn speak volumes about the paradigmatic status of orthodox economics, according to our operational definition. First, whatever else we might think about orthodox economics, it does qualify as an interlocking set of ideas that informs action. Second, there is the claim that it is scientific. Third, there is the claim that it is universal and therefore can be extended to all the social sciences, not just economics.

The roots of orthodox economics can be traced all the way back to the origin of the profession and the desire to place economics on a scientific foundation at a time when this meant emulating Isaac Newton (Dyer 2024).2 The assumptions required to formulate a “physics of social behavior” and make it respectably mathematical are the “adaptive peak” or “basin of attraction” that orthodox economics has been trapped within for over 200 years.

When we evaluate orthodox economics by our two criteria, we can say that it fails miserably on both counts. The unreality of Homo economicus and frictionless markets at equilibrium has been pointed out so many times that it need not be repeated. In Milton Friedman’s (1953) essay on positive economics, he acknowledged the absurdity of these assumptions and justified them with the empirical claim that firms and markets behave as if the assumptions are true and that at the end of the day, the paradigm leads to effective policies. In other words, over 75 years ago, Friedman abandoned the first criterion and relied upon the second criterion. But now we know that orthodox economics has failed miserably on the second criterion, also. If ever a paradigm deserves to be rejected on both criteria, it is this one.

It is a mistake to focus too narrowly on the economics profession. The idea that all things social can only be understood in terms of the motives and actions of individuals (methodological individualism) extends more broadly throughout the social sciences (Hodgson 2007). In biology, the study of evolution in the 20th century became restricted to Mendelian genetics and then even more reductionistically to molecular biology. Everything that evolved was said to be adaptive at the level of individuals and their selfish genes (Dawkins 1976). Individualism and reductionism were like a tide lifting all disciplinary boats.

In retrospect, we can see that what passed as science before and during the 20th century was a de facto denial of complexity. For all their power, formal mathematical models are extremely limited by the assumptions that they must make and the number of variables that can interact in a nonlinear fashion. The same is true for empirical experiments, which at most can vary only a few factors and must hold everything else constant. The entire world of complex systems lies beyond the formal methods of science, a point to which I will return below.

Identifying the problem of no paradigm. Heilbroner (2004) had a point when he called the other social sciences (e.g., anthropology, sociology, political science, history) “softer” than orthodox economics. Collectively or even within their own disciplinary boundaries, they do not provide an interlocking set of ideas worthy of being called an alternative paradigm. Instead, they are like an archipelago of islands with little communication among islands. Each “island” might have its interlocking set of ideas, but there is no way to integrate across islands.

To demonstrate this for yourself, the next time you are with a group of people or speaking to an audience, ask them to recall a thinker who has especially influenced them—a proverbial giant upon whose shoulder they are standing. Then have each person name their giant to their neighbor. In many cases, one person’s giant is completely unknown to the other person!

The “archipelago” nature of knowledge and practice is a severe limiting factor in our understanding of the world and our ability to act upon our knowledge. It also largely explains why orthodox economic thinking, for all its unreality and toxic consequences, has been able to invade other academic disciplines and public policy sectors on the strength of its coherence. Replacing the currently dominant paradigm requires another interlocking set of ideas that qualifies as a new paradigm.

Articulate and evaluate a new paradigm that can be widely agreed upon: A combination of complex systems science and evolutionary science can legitimately be called a new paradigm (Beinhocker 2006; Wilson and Kirman 2016; Wilson and Snower 2024). Both are substantially new within the last 50 years, although for different reasons.

The complexity of the world has been verbally acknowledged and reflected upon since antiquity and in all cultures. As already mentioned, however, formal mathematical models quickly hit a “complexity wall” beyond which they cannot go, such as the three-body problem in physics or multi-locus population genetics models with non-linear interactions among the loci. The advent of computer simulation modeling was required to go beyond the complexity wall, which did not take place until the second half of the 20th century (Simon 1969, Gleick 1987, Meadows 2008). By now, many people are at least moderately familiar with a “toolkit” of concepts from complex systems science, such as extreme interdependence, non-equilibrium dynamics, multiple basins of attraction, sensitive dependence on initial conditions, complex emergent properties of simple interactions, and scaling laws. Complex systems science is not a mere island in an archipelago. It is an interlocking set of ideas that applies to all the islands of the archipelago.

Evolutionary science is substantially new within the last 50 years because for most of the 20th century it was narrowly confined to the study of genetic evolution—the modern synthesis that I briefly described earlier. More recently, Darwinism is defined as any process that combines the three ingredients of variation, selection, and replication, no matter what the proximate mechanisms (Beinhocker 2011; Campbell 1974; Jablonka and Lamb 2006; Plotkin 1994).

This includes human cultural evolution, the individual person as an open-ended evolutionary unit (Skinner 1981), and computerized evolutionary algorithms (AI). Generalized Darwinism comes with its own “toolkit” of concepts, including proximate and ultimate causation, the need to study all products of evolution from functional, historical, mechanistic, and developmental perspectives, multilevel selection, dual inheritance, and core design principles for governance and adaptability (Wilson 2019). Like complex systems science, evolutionary science is not an island but an interlocking set of ideas that applies to all living systems and therefore all islands of the archipelago other than non-living physical systems (e.g., the weather).

The two “toolkits” describe the new complexity/evolution paradigm in considerable detail. Describing them as toolkits also conveys their pragmatic and utilitarian potential. Like a carpenter or plumber with their toolkits, the complexity/evolutionary theorist can show up at the worksite, select the appropriate tools, get the job done, and move on to the next job.

Is it possible to evaluate the new paradigm according to our two criteria? The new paradigm is far, far more in accord with scientific knowledge than the orthodox economic paradigm. In addition, there is a surprising amount of support for its practical applications, based on evidence that already exists but has been obscured by the old paradigm (e.g., Wilson 2023). The evidence has been “hiding in plain sight”, awaiting a new perspective to see it. And there is a growing body of evidence based on new applications of the paradigm (e.g., Wilson et al. 2023).

Reaching a consensus on the new paradigm: At a high altitude--the proverbial 30,000 ft view--it should be easy for large numbers of people to identify with and start interacting within the new paradigm. Who can disagree with the statement that all our constructions are both complex and in some sense a product of evolution?

As we attend to details, however, numerous disagreements are likely to arise that will need to be worked out. This is only to be expected—and should even be welcomed-- when we remember that a paradigm is a container for productive disagreement and not a choir singing in unison. Also, participants of the debates will come from different disciplinary islands, and work will be required to establish a common vocabulary.

To anticipate some of the conversations that will take place:

• For many people, the word “Darwinism” signifies the moral justification of inequality (so-called social Darwinism). Work will be required to establish what is meant by the term and how the new paradigm is centered on cooperation and inclusion.

• During its gene-centric period, the study of evolution downplayed organisms as complex living systems and denied any direction or purpose to evolution other than adaptation to the immediate environment. The new paradigm overcomes these limitations in what’s sometimes called the “extended evolutionary synthesis” (Laland et al. 2015; Noble and Wilson 2025).

• Two meanings of the key phrase Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) need to be distinguished (Wilson 2016): A complex system that is adaptive as a system (CAS1) and a complex system composed of agents following their respective adaptive strategies (CAS2). Work will be required to establish that CAS1 systems do not automatically emerge from CAS2 systems and to identify the special conditions required for this to happen, since it is the basis of all prosocial change efforts.

Using the new paradigm to inform how we act upon the world across all scales and topic domains: Despite its recency, the new paradigm is “shovel-ready” for practical applications. Whenever possible, activities should take the form of learning by doing. Every prosocial change effort, no matter what the scale or topic domain, should be treated as an experiment in the cultural evolution of complex systems.

I now invite my colleagues to expand upon my short essay with their commentaries.

Notes:

[1] According to Provine (1986), Sewall Wright invoked the metaphor of adaptive landscapes in three different ways that are incommensurable with each other and was unaware of this until Provine pointed it out to him.

[2] Go here for a review of Ricardo’s Dream (Dyer 2024) and podcast with its author.

Literature Cited:

Aldrich, H. E., Hodgson, G. M., Hull, D. L., Knudsen, T., Mokyr, J., & Vanberg, V. J. (2008). In defense of generalized Darwinism. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 18(5), 577–596.

Beinhocker, E. D. (2006). Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Harvard Business School Press.

Beinhocker, E. D. (2011). Evolution as computation: Integrating self-organization with generalized Darwinism. Journal of Institutional Economics, 7(3), 393–423. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137411000257

Campbell, D. T. (1974). Evolutionary epistemology. In P. A. Schilpp (Ed.), The Philosophy of Karl Popper (pp. 413–463). Open court publishing.

Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish gene (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

Dyer, N. (2025). Ricardo’s Dream: How Economists Forgot the Real World and Led Us Astray. Bristol University Press.

Friedman, M. (1953). Essays in Positive Economics. University of Chicago Press.

Gleick, J. (1987). Chaos: Making a new science. Penguin Books.

Goodman, C. S., & Coughlin, B. C. (2000). The evolution of evo-devo biology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97, 4424–4425.

Heilbroner, R. (2004). Economics as Universal Science. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 71(3), 615–632.

Hodgson, G. M. (2007). Meanings of methodological individualism. Journal of Economic Methodology, 14(2), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501780701394094

Jablonka, E., & Lamb, M. J. (2006). Evolution in Four Dimension: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioral, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life. MIT Press.

Laland, K. N., Uller, T., Feldman, M. W., Sterelny, K., Müller, G. B., Moczek, A., Jablonka, E., & Odling-Smee, J. (2015). The extended evolutionary synthesis: Its structure, assumptions and predictions. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1813), 20151019. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.1019

Masterman, M. (1970). The Nature of a Paradigm. In A. Musgrave & I. Lakatos (Eds.), Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge: Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science, London, 1965 (Vol. 4, pp. 59–90). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139171434.008

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems Chelsea Green.

Noble, D., & Wilson, D. S. (2025). Is Neo-Darwinism Enough?: The Noble-Wilson Dialogue on Evolution (J. A. Barham, Ed.). Inkwell Press.

Plotkin, H. (1994). Darwin Machines and the nature of knowledge. Harvard University Press.

Provine, W. P. (1971). The Origins of Theoretical Population Genetics. University of Chicago Press.

Provine, W. B. (1986). Sewall Wright and Evolutionary Biology. University of Chicago Press.

Simon, H. A., & Laird, J. E. (1969/2019). The Sciences of the Artificial, reissue of the third edition with a new introduction by John Laird. The MIT Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1981). Selection by Consequences. Science, 213, 501–504.

Wilson, D. S. (2016). Two meanings of complex adaptive systems. In Complexity and Evolution: A New Synthesis for Economics (pp. 31–46). MIT Press.

Wilson, D. S. (2019). This View of Life: Completing the Darwinian Revolution. Pantheon/Random House.

Wilson, D.S. (2023). Evolution, Complexity, and the Third Way of Entrepreneurship. This View of Life. https://www.prosocial.world/posts/evolution-complexity-and-the-third-way-of-entrepreneurship

Wilson, D. S., & Kirman, A. (2016). Complexity and Evolution: Toward a New Synthesis for Economics (D. S. Wilson & A. Kirman, Eds.). MIT Press.

Wilson, D. S., Madhavan, G., Gelfand, M. J., Hayes, S. C., Atkins, P. W. B., & Colwell, R. R. (2023). Multilevel cultural evolution: From new theory to practical applications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(16), e2218222120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2218222120

Wilson, D. S., & Snower, D. J. (2024). Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm. Economics, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/econ-2022-0070

Wilson, D. S., Styles, R., & Atkins, P. W. B. (2024). Conscious Multilevel Cultural Evolution: Theory, Practice, and Two Case Studies. This View of Life. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.11237061