“Hundreds of years from now, if an anthropologist finds your bones, they will say you are either male or female.” Versions of this meme litter social media, reinforcing the idea that biological traits, like one’s skeleton, are more meaningful than a person’s lived identity. It reads as though the existence of anthropologists somehow negates the existence of trans and gender nonbinary individuals.

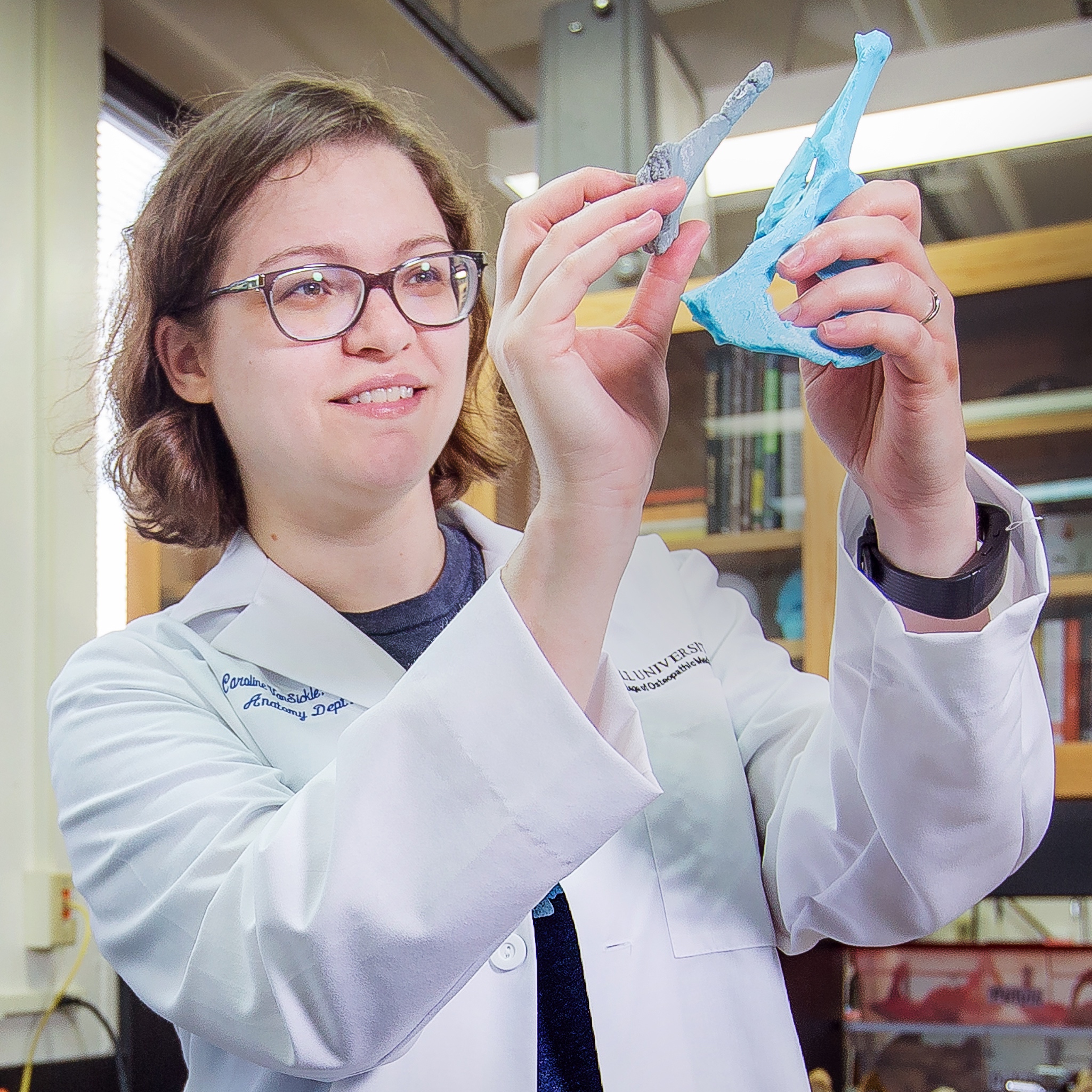

I am an anthropologist, one who studies sex differences in the human skeleton. I can tell you that my ability to estimate (not determine!) the sex of a skeleton from 100 years ago is limited by the preservation of the skeleton and what is known about the person’s life. I could guess at the person’s sex, because that is what the methods used by anthropologists are designed to do, but for some individuals, that guess may be highly unreliable.

In the introduction to this series, Joan Roughgarden (2025) described the global political trends to define sex solely based on reproductive cell (gamete) size—large gametes (eggs) are produced by females, and small gametes (sperm) are produced by males. Agustín Fuentes and Nathan Lents (2025) added additional definitions of sex used in biology, including genetic sex, chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, genital-anatomical sex, morphological sex, and hormonal sex. In this essay, I add yet another definition: skeletal sex.

Since a skeleton does not provide information about gonad morphology or gamete production capabilities, scientists studying skeletal remains had to develop methods to define sex solely from skeletal remains. These methods involved a lot of anatomical data collected from large samples of known-sex skeletons, all of which were used to calculate the reliability of a sex estimation based on a particular trait or measurement.

Features of the pelvis were identified as the best skeletal indicators of sex, as generally females will have a short sacrum, wide greater sciatic notch, long superior pubic ramus, and wide subpubic angle, all of which expand the pelvic cavity for birth. Yet, morphological traits vary considerably in their individual accuracy: while the ventral arc of the pubis may accurately estimate sex 85% of the time, the shape of the obturator foramen may do so only 58% of the time (Klales, 2020). Estimating sex based pelvic measurements can yield accuracy rates over 90% when multiple measurements are combined into a calculation (Baumgarten & Kenyon-Flatt, 2020; Santos et al., 2020). However, these measurements often depend on complete bones for evaluation, which is rarely the use case for anthropologists, and any measurement of size may vary more between populations than between sexes.

Where a person lived, who they were related to, what their diet looked like, how active they were, and what their access to health care was can all influence pelvic shape. Pelvic shape is not static; it is shaped initially by the hormones present in utero, grows and develops throughout childhood, is remodeled again by the hormones present at puberty, and then continues to remodel slightly throughout adulthood (Huseynov et al., 2016). Thus, sex estimation methods developed assuming a static and universal difference between males and females have some issues that hinder their reliability.

First, the samples used to develop sex estimation methods were often not representative of a global population. For example, many methods were initially developed and tested on the Robert J. Terry Collection, which included 1,728 working-class individuals from Missouri, most of whom had been born before the year 1900 (Hunt & Albanese, 2005; Klales et al., 2020). Since the skeleton reflects a person’s diet, access to health care, genetics, and activity patterns, it is unlikely that the Terry Collection is an accurate representation of the range of skeletal variation seen across humans with varied lifestyles and experiences. While some methods have been validated on broader samples (for example, see Santos et al., 2020), not all have, leaving questions about their accuracy when used on an individual from an unknown population.

Second, human sexes do not differ dramatically in skeletal traits. There is a considerable range of overlap between males and females for most traits used to estimate sex. This fact is acknowledged in the methodologies, which frequently score individuals as “likely male”, “likely female”, or “undetermined”. Undetermined means the individual falls within the range of variation that could be either male or female, so that trait cannot distinguish sex in that individual. Even within a sex, pelvis shape can vary considerably; for example, female pelves come in multiple shapes beyond the version usually shown opposite a male (VanSickle et al., 2022). Such overlap means that anthropologists really are estimating, as opposed to determining, the sex of a skeleton when they study it. Some individuals simply defy classification, and we acknowledge that is a normal part of our science.

Third, all sex estimation methods classically used by anthropologists are designed to classify a human as either male or female, which means they are inherently unable to recognize any other categories. Intersex is an umbrella term for a variety of differences of sexual development that normally occur in humans. While these variations can affect genes to reproductive organs, some versions affect hormone production by the gonads (Garofalo & Garvin, 2020). This is noteworthy because reproductive hormones, especially during puberty, strongly influence the shape of the developing pelvis (Huseynov et al., 2016). Though we currently lack the necessary data to understand how to recognize an intersex skeleton, it is reasonable to think that hormonal variations caused by being intersex would affect pelvis shape.

Fourth, and most importantly, given the typically transphobic usage of the meme, sex estimation methods do not consider a person’s gender. Despite trans and gender diverse individuals being disproportionally susceptible to homicides, forensic anthropologists remain unable to say how frequently such individuals are represented in their casework because they lack the tools to identify them (Tallman et al., 2021). We lack trans-focused studies to assess the effects of gender affirming surgeries or hormone therapies on the skeleton. This gap means that cases involving missing trans or gender diverse people may go unsolved due to uncertainty over how to recognize gender affirming interventions from the skeleton.

If I were directed to estimate sex from a 100-year-old skeleton today, I would likely come up with an answer of male or female. Without knowing anything else about the individual, I may have concerns over whether the method I used was appropriate for the individual’s population and health status. I would expect some of the features to be scored as “undetermined,” which may mean prioritizing more clear results even if they come from less reliable anatomical regions. I might wonder if the individual could have been intersex, and be left wondering, since there is currently no way to assess intersex variation from the skeleton. I might further wonder if they had been trans or gender diverse, if they had undergone gender affirming surgeries or hormone therapies that might affect their skeletal morphology, and whether or not I had appropriately considered this in my estimation.

Yet, 100 years from now, I hope an anthropologist is able to do more. I hope they have access to methods designed to characterize male, female, and intersex skeletal variation instead of erasing intersex individuals. I hope they have robust data on how gender affirming interventions change the skeleton of trans and gender diverse individuals, which would allow those individuals to be recognized. I hope that if your skeleton were found by an anthropologist in the future, they would be able to see you as more than just your sex assigned at birth.

References:

Baumgarten, S. E., & Kenyon-Flatt, B. (2020). Metric methods for estimating sex utilizing the pelvis. In Sex Estimation of the Human Skeleton (pp. 171–184). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815767-1.00011-0

Fuentes, A., & Lents, N. (2025, November 18). Beyond the Binary: The Compounding Complexity of Biological Sex. This View of Life Magazine. https://www.prosocial.world/posts/beyond-the-binary-the-compounding-complexity-of-biological-sex

Garofalo, E. M., & Garvin, H. M. (2020). The confusion between biological sex and gender and potential implications of misinterpretations. In Sex Estimation of the Human Skeleton (pp. 35–52). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815767-1.00004-3

Hunt, D. R., & Albanese, J. (2005). History and demographic composition of the Robert J. Terry Anatomical Collection. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 127(4), 406–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20135

Huseynov, A., Zollikofer, C. P. E., Coudyzer, W., Gascho, D., Kellenberger, C., Hinzpeter, R., & Ponce de León, M. S. (2016). Developmental evidence for obstetric adaptation of the human female pelvis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(19), 5227–5232. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517085113

Klales, A. R. (2020). Sex estimation using pelvis morphology. In Sex Estimation of the Human Skeleton (pp. 75–93). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815767-1.00006-7

Klales, A. R., Long, H., & Willsey, C. (2020). A history of sex estimation of human skeletal remains. In Sex Estimation of the Human Skeleton (pp. 3–10). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815767-1.00001-8

Roughgarden, J. (2025, November 11). Sex, Gender Diversity, and Evolution: Introduction. This View of Life Magazine. https://www.prosocial.world/posts/sex-gender-diversity-and-evolution-introduction

Santos, F., Guyomarc’h, P., Cunha, E., & Brůžek, J. (2020). DSP: A probabilistic approach to sex estimation free from population specificity using innominate measurements. In Sex Estimation of the Human Skeleton (pp. 243–269). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815767-1.00015-8

Tallman, S., Kincer, C., & Plemons, E. (2021). Centering Transgender Individuals in Forensic Anthropology and Expanding Binary Sex Estimation in Casework and Research. Forensic Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.5744/fa.2020.0030

VanSickle, C., Liese, K. L., & Rutherford, J. N. (2022). Textbook typologies: Challenging the myth of the perfect obstetric pelvis. The Anatomical Record, 305(4), 952–967. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24880

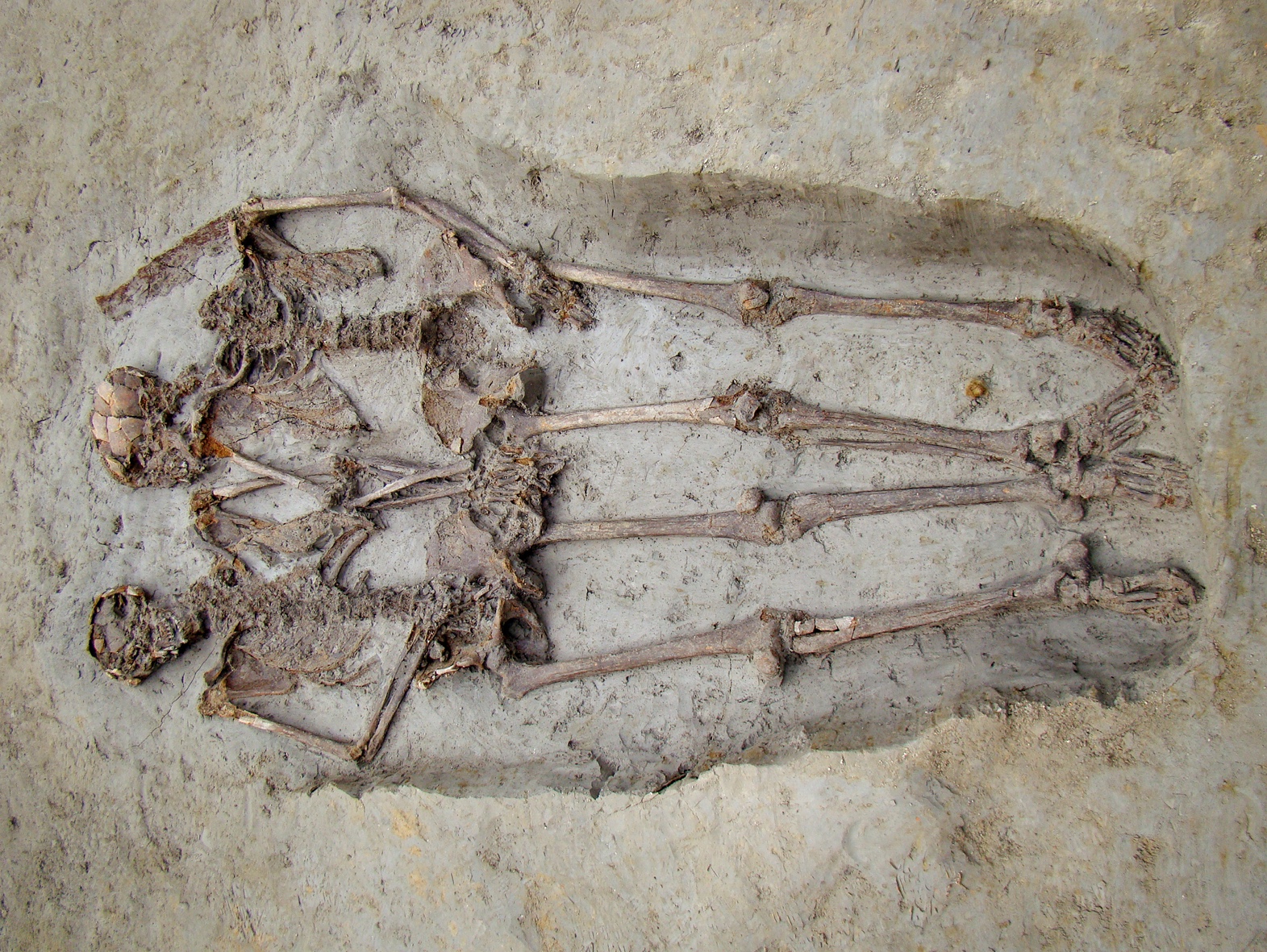

Cover Image: Lovers of Modena, skeletons buried between the 4th and 6th century AD with their hands interlocked and whose skeletons both appear to be male. Photo by Paolo Terzi, courtesy of Archivio fotografico Museo Civico di Modena.