Sexual bodies are extremely diverse in nature. Biologists often grapple with the difficulty of explaining this diversity, and we resort to simplified categorization that allows us to converse and develop programs of inquiry. Yet categories are agreed upon for the purpose of generalization, and do not therefore explain all variation. Biological categories are created by scientists, and most of the time do not represent intrinsic properties of the objects or subjects or study. Ultimately, every individual organism has unique characteristics that would make the task of general knowledge construction extremely difficult in the absence of simplification. However, as our knowledge in the field advances, biologists are responsible for ensuring that our approaches are updated to better represent our growing understanding of biological phenomena that explain individual variation, rather than allowing “traditional” yet outdated explanations that exclude individuals who challenge our neat, yet incomplete, explanations.

Variation is the inevitable result of complexity. Developmental biological processes that occur throughout the life of individuals (not just in utero) are among the most complex in nature. Building and growing a body relies on interconnected and ongoing conversations between genes, the proteins they produce, and the environment. As genes are expressed, they change their environment, and as the environment changes, gene expression is also influenced. This results in endless variation that is not just simply a by-product of development but crucial for evolution. Variation helps cope with the unexpected in biology. Therefore, variation is not only a natural outcome of the interactions between genes and the environment, but also is necessary for species survival in the face of uncertainty. My own field of study, the evolution of genital morphology, can offer a small glimpse into what some of these complex processes are like, and the obvious need to revise traditional assumptions when it comes to sexual traits.

Genitalia are often thought of as a binary sexual trait, and in humans, we use genitalia to assign sex at birth. The sex of a baby will be declared based on the appearance of their external genitalia, and that declaration will often make sense if there is correspondence between gonads, sex chromosomes, hormones, and genitalia. Sometimes, however, sex assignments at birth are incorrect because there is disagreement between the external morphology and the internal gonads, and/or the sex chromosomes. Or no sex can be assigned because the complexity inherent to genital development sometimes results in ambiguous genital morphologies.1 And while it may be tempting to think of these occurrences as rare or anecdotal, when they happen repeatedly, generation after generation, they become an integral part of the biological make-up and natural variation of a species.

I have been examining animal genitalia for the better part of the last 20 years, marveling at the extraordinary diversity that exists in their form and function, and trying to fill in gaps in our understanding of why this diversity exists within and across species. In my research, I have been correct, incorrect, and confused when trying to determine if the organism in front of me clearly has a penis, a clitoris, a vagina, is intersex, reproductively suppressed, or is simply a juvenile. Why would an expert ever be confused about this? Sexual differentiation is extremely variable across terrestrial vertebrates, including lizards and snakes, turtles, crocodiles, birds, and mammals. In all these groups, all individuals begin as undifferentiated organisms, and during early urogenital development, a pair of bumps–the phallic bodies–appear in the cloacal lip. This is the undifferentiated phallus that will often become a penis, a clitoris, or something in between. The development of genitalia is often a lifelong process, where final differentiation will occur only when individuals are ready to become reproductive. Before then, genitalia can be inconspicuous and undifferentiated, making it impossible to ascertain from external examination alone whether that individual is a male or a female given its phallus morphology. Often, a vaginal closure membrane will be present, so there is no vaginal opening either. In some species, this non-reproductive state can last a lifetime, and some organisms may die never having produced any offspring because they are reproductively suppressed by larger or older group members. Naked mole rats and meerkats are good examples of these reproductively suppressed species. In naked mole rats, for example, the external genitalia are completely undifferentiated in non-reproductive individuals, so if I were to examine a non-reproductive adult, its genitalia would not reveal much about its sex.

Sometimes, genital examination suggests one sex, but further examination reveals another, a type of genital variation that we often refer to as intersex. When I began my research, my observations of animals that did not fit the expected genital binary were rare, and I only found the obvious. I dissected two ducks with gorgeous plumage and well-developed testes, only to be stumped by the complete absence of a penis. Unable to click the M or F box in my data sheet, I wrote in my notes: “intersex (?)”. These individuals made sperm, but they lacked a penis, and since the penis is always out of sight in birds, I imagined they still attracted a mate and could reproduce if their sperm could swim long enough inside the oviduct. And I wondered whether these sex variations affected these ducks’ day-to-day life: Did they realize they were different? Did their mates know?

Later, while teaching vertebrate anatomy, we were thrilled to get a spiny dogfish shark with no intromittent organs on the pelvic fins–often a female–to dissect, as most of the class had sharks with claspers–often a male–but when we opened its body cavity, we saw well-developed testes, and no ovaries, uterus, or vagina. Intersex for sure (now I knew!). And my students and I talked about what the life of this shark was like. Did its morphology influence its social life? Maybe it mated with sharks with claspers, or caroused with clasperless sharks, or maybe it did not want to mate at all. Who is to say? We acknowledge that individuals are complex, whole creatures with their own stories.

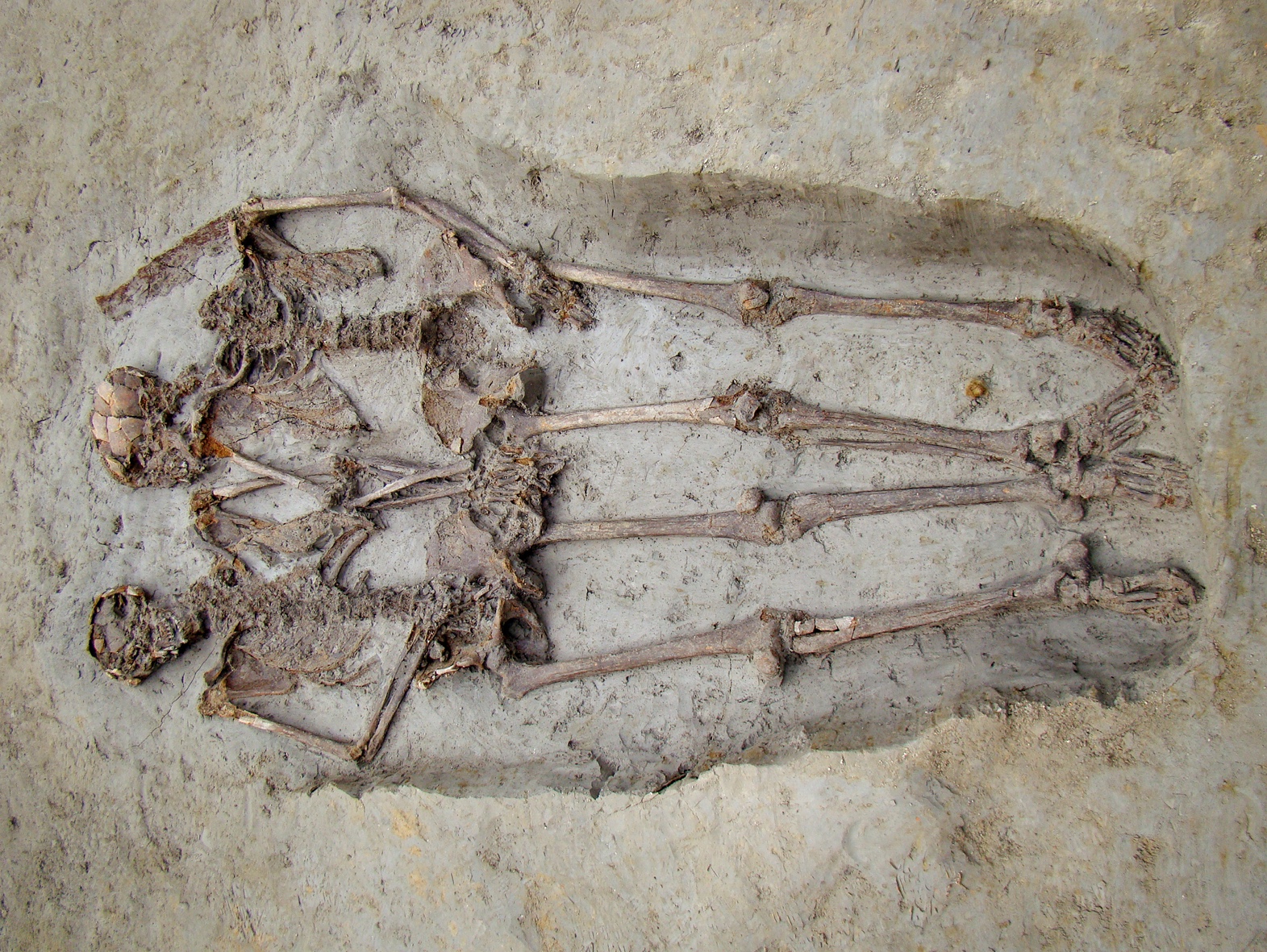

We then started paying more attention when we dissected our specimens. And because we did, we started finding intersex variations more often. In snakes, intromittent genitalia are called hemipenes as there are two of them, kept inside out in the cloaca, and corresponding paired structures in females called hemiclitores. In pythons and rattlesnakes, where we have examined about 100 individuals in each group, we have found two individuals in each with well-developed hemipenes and testes, but also with a vaginal pouch–certainly intersex–a percentage similar to the 2% intersex suggested by Anna Fausto-Sterling for humans. The golden lancehead snake (Bothrops insularis) living on an Island off the coast of Brazil is reported to have a very high percentage of intersex, where many individuals have well-developed vaginas and ovaries, as well as very large hemiclitores, while others have much smaller hemiclitores. We know little about this phenomenon in snakes, but the book Middlesex comes to mind… places where human intersex conditions are common and become accepted by all.

But the surprising variation of genitalia goes well beyond the obvious and/or/neither. While studying ducks, I learned that the penis changes in size seasonally, growing in the spring and shrinking in late summer, suggesting that penis size is under hormonal control that responds to the light cycle. I became curious as to whether we could modify the size of the penis by changing the social environment instead of the seasonality, if competing with other individuals for access to mates influenced the evolution of the penis in the first place. Even though the idea seemed far-fetched at the time, I expected that the social environment would influence the phenotype in some way. So, I placed some ducks in social competition environments with many males and fewer females, and others in a male/female pair where they did not have to compete.

The result was mind-blowing: In one species, the lesser scaup, just as I expected, penises were larger on average in the competition groups, suggesting that this trait is influenced by levels of competition. In the other species, the ruddy duck, larger individuals reproductively suppressed every other male in the competition groups, and as a result, only the larger male had a fully developed penis for the whole reproductive season. Everyone else did not grow a functional penis and did not change into the typical reproductive colors. How they were treated changed their penis morphology! These experiments did not add toxins or drugs to the body (known morphology disruptors), but simply manipulated social interactions, which are the daily reality for these ducks. And their genitalia changed. The social environment, therefore, had a huge impact on their phenotype… The part of the phenotype that we call Primary.

Usually, we think of penises as intromittent organs that enter the vagina, or terminal portion of the oviduct that interacts with the penis, to deposit sperm close to eggs and facilitate internal fertilization. But in some species, like in Brazilian cave flies and sea horses, the egg-bearing individuals have penises and deposit their eggs inside the vagina or the uterine pouch of the males for fertilization to take place. Sometimes, as is the case with 97% of all birds, there is no penis at all, even when individuals make sperm; internal fertilization without intromission and without a penis. In this case, we refer to males based on their plumage, or gonads, or behavior, but not their genitals. Most surprisingly, though, sometimes everyone has a vagina! Just this year, while looking at genital variation in red-tailed boas, we found that all individuals have vaginal pouches that have the same shape. Some of these pouches are bigger than others, but they overlap significantly, and some individuals have ovaries and hemiclitores, and some have hemipenes. We only learned this because we were examining all individuals with hemipenes for the presence of a vaginal pouch to see if some individuals were specifically intersex, but found that everyone has a vagina, while not everyone has hemipenes. Then, either we have to change our functional definition of a vagina, or having a vagina does not make a red tail boa a female. Confused? You bet. I am not supposed to have feelings about this discovery, but I do, and I feel awe and amazement and joy that I get to study these complex, beautiful, and fascinating structures that defy our rules and boxes.

These are only observations on genital variation, neglecting what may be going on with the sex chromosomes or the hormones, and important levels of variation in assigning intersex. A recent paper on birds concluded that 3-6% of all 500 examined individuals in 5 Australian species were intersex; they had mismatches between their sex chromosomes and their sexual characteristics; for example, a genetic male was reported laying an egg, a report that defies the idea of intersex as evolutionary non-functional dead-ends. They found this mismatch between sex chromosomes and phenotype by genotyping all their samples. Proof that in science, we generally find only what we are looking for. If we look for evidence of a male and female binary, we will find it, and we will explain away exceptions as anecdotes and rare events. If we look to describe all the existing variation, we will certainly find that too, and struggle as I do to categorize and describe, but at least we will get closer to the truth.

Avoiding morality lessons from nature is a common and useful rule in academic hallways, but when people weaponize nature to argue that something unnatural is wrong, or to argue that there are only two inflexible sexes, then it is time to show what nature really does. Nature does whatever selection has shaped; what has been good to spread genes. And “all males have a penis, and all females have a vagina” is not it, and it is not true. Being plastic, being diverse, and being flexible when it comes to genitalia is better than the alternative. It’s not easy or convenient, but it is accurate. Complex as that.

Notes:

- Babies born with ambiguous genitalia have often been subjected to medically unnecessary surgeries to solve the social discomfort associated with an inability to clearly determine sex. These practices are thankfully ending after causing untold harm. day-to-day.

References:

Brennan, P.L.R., Gereg, I., Goodman, M. Feng, D. and Prum, R.O. 2017. Evidence of socially induced phenotypic plasticity of penis morphology and delayed reproductive maturation in waterfowl. The Auk. 134. DOI: 10.1642/AUK-17-114.1.

Campos Garcia, V., dos Santos Amorim, L. G., & Almeida‐Santos, S. M. (2022). Morphological and structural differences between the hemipenes and hemiclitores of golden lancehead snakes, Bothrops insularis (Amaral, 1922), revealed by radiography. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia, 51(4), 557-560.

Gredler, M. L., Larkins, C. E., Leal, F., Lewis, A. K., Herrera, A. M., Perriton, C. L., ... & Cohn, M. J. (2014). Evolution of external genitalia: insights from reptilian development. Sexual Development, 8(5), 311-326.

Hall, C. A., Conroy, G., Jelocnik, M., Kasimov, V., Gillet, A., Portas, T., ... & Potvin, D. A. (2025). Prevalence and implications of sex reversal in free-living birds. Biology Letters, 21(8), 20250182

Keeffe, R. Hedrick, B, Bartoszek, I., Easterling, I. Brennan, P.L.R. 2025. Morphological Variation in the Genitalia of the Burmese Python. Journal of Morphology. 86(4), e70045

Keeffe et at. 2025. Shape differences in the genitalia of rattlesnakes in a hybrid zone: The keys are the same but the locks are different. Evolution meeting

Machado, et al 2025. Bilobed hemipenes and a heart-shaped mystery: exploring the mismatched morphology of boa constrictor genitalia. Evolution, Athens, GA. June 20-24, 2025.

Seney, M. L., Kelly, D. A., Goldman, B. D., Šumbera, R., & Forger, N. G. (2009). Social structure predicts genital morphology in African mole-rats. PLoS One, 4(10), e7477